|

Great Caricatures • Articles & Galleries • |

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Books

on Honoré Daumier |

|||||||||||

©

Great Caricatures

2023

![]() Censorship

in 19th Century France

Censorship

in 19th Century France ![]()

Caricatures & Censorship

To view a gallery of censor-related caricatures, see Caricature

vs. the Censor.

F |

rench political caricatures of the 19th century chronicle the gradual, |

often-violent end of the Monarchy and the emergence of a democratic state. French rulers strictly regulated the popular press, especially satirical images. In a time when a large percentage of the population couldn't read, these images were seen as a greater threat to the established order than the printed word. French caricaturists worked under gov- ernment-imposed censorship throughout most of the 19th century. Artists and editors were imprisoned, fines were levied and newspapers were seized. Offenders were rigorously prosecuted for "press crimes," which authorities interpreted as alleged defamatory and subversive attacks on the government. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Timbre Royal" was

applied to publications approved by French authorities during

the 19th century.

![]()

The first European newspaper was the Gazette de France published in 1631. It served as a propaganda tool for the monarchs from Louis XIII to Louis XVI. There was no political criticism in the press or freedom of publication for over 150 years.

During the 1700's, the art of engraving was unrestricted but the sale of prints was subject to censorship through the lieutenant general of the police. Offenders could pay with their lives. One caricaturist was burned alive for portraying Louis XIV with his mistresses.

|

|

|

|

'Destruction

of November 1, 1798 |

|

|

|

|

Censors prevented the distribution of prints that were considered harmful to "religion, the general good and the peace of the State, and the purity of morals." Political prints from England were also seen as a threat and attempts were made to stop them before they entered France. But this ban on imported prints had limited effect and a large black market developed for English engravings.

In 1789, the state's financial crisis led to social turmoil that triggered a revolution. Weeks later, the revolutionaries formed the Constituent Assembly and adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man which embodied the principles of Liberté, Egalité, and Fraternité (Freedom, Equality, Fraternity). It stated that the free communication of ideas and opinions is a fundamental human right and that every citizen should be allowed to speak, write and print freely. As a result, 350 journals and periodicals came into existence.

But this right to free speech was short-lived for caricature. On July 31, 1789 a censor for caricatures was appointed in Paris.

This declaration was also included in the Constitution of 1791 (the first written constitution in Europe), and the press was unregulated until the summer of 1792 when the radical opponents of the monarchy became alarmed at the popularity of pro-royalist journals and pamphlets. Editors of royalist newspapers were threatened and intimidated. Later, during the Terror, many royalist editors were guillotined. The monarchy's Committee of Public Safety censored and regulated all newspapers. Eventually their publication was suspended altogether.

The declaration appeared again in the Constitution of 1795.

|

|

||

|

'est

de deux! ... 1830 |

||

|

|

||

By 1811, only four newspapers were left in Paris. Official, commercial, scientific and learned periodicals were allowed to publish if they contained no political content.

Censorship was lifted in 1814, when Napoleon was defeated and the Bourbon monarch Louis the XVIII was restored to the throne. In 1820, the assassination of the King's nephew led to the suspension of civil rights and regulation and censorship of newspapers and pamphlets.

|

|

|

|

'L'ordre

public September 1831 |

|

|

|

|

Ten years later in July of 1830, the repressive policies of Charles X (Louis XVIII's successor) led to a spontaneous rebellion in Paris. Three days of rioting forced the king to flee and eventually abdicate. A group of political leaders desperately sought to preserve the monarchy. They invited the duc d'Orléans to become the new monarch, on the condition that he swear an oath to defend a revised constitution called the Charter of 1830. The Charter guaranteed freedom of religion, promised equality before the law to all citizens, and declared private property to be inviolable. The Charter also stated that censorship would never be reestablished.

The duc d'Orléans assumed the title of Louis Philippe I. At the beginning of his reign he was called the "Citizen King." Louis Philippe was the only French monarch who unexpectedly came to power as the result of a popular uprising against his predecessor, but the longer he ruled, the more intent he became on erasing his revolutionary origins.

|

|

|

|

La Caricature |

|

|

|

|

Charles Philipon and the Business of Caricature

Charles Philipon, a man once described as "journalism made flesh," collaborated with his brother-in-law Gabriel Aubert's lithograph business to found two journals dedicated to propagandizing through pictures: La Caricature and Le Charivari.

Philipon gathered a team of writers and artists to challenge the government and wage "warfare every day upon the absurdities of every day." His printers worked day and night, combining letterpress and lithography. They published up to 2,000 newspapers a day with caricatures on themes of politics and social satire by Daumier, Grandville, Gavarni, Traviés, and many others.

In 1832, Philipon claimed to have suffered, "twenty seizures, six prosecutions, three convictions, over 6,000 francs in fines, 13 months of prison, and persecutions.” His publisher, Aubert, was prosecuted eight times between 1831 and 1834.

Censorship was once again imposed in 1835. As part of an address to the French legislature in 1835, the Minister of Commerce declared, "there is nothing more dangerous, gentlemen, than these infamous caricatures, these seditious designs," which "produce the most deadly effect." Censorship was abandoned in 1848 and restored in 1852. It was briefly removed between 1870 and 1871 and finally abolished in 1881.

André Gill, La Lune and L'Eclipse

|

|

|

|

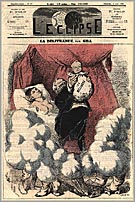

Cover illustration of L'Eclipse |

|

|

|

|

In the 1860s and 1870s, André Gill was the unchallenged master of caricature in France. Gill drew full-page colored illustrations of famous personalities that were published on the covers of large-format caricature journals. When displayed on newsstands, they functioned as political posters. His work for La Lune generated a circulation of 40,000 copies.

Throughout his career he battled government censors, who would sometimes allow his work to be published only after the faces of his subjects were removed from the illustration.

During the 19th century, over 350 caricature journals were established. This period has been called "The Age of Gold" of French caricature.

To be continued ...